The Stalking Moon

|

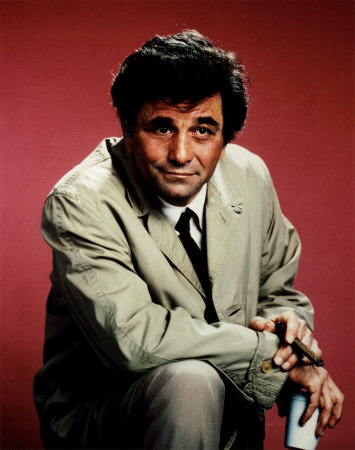

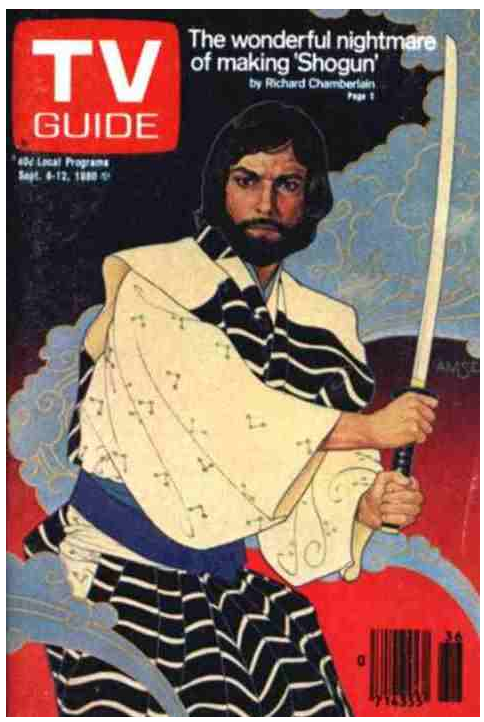

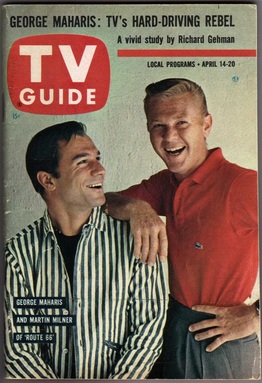

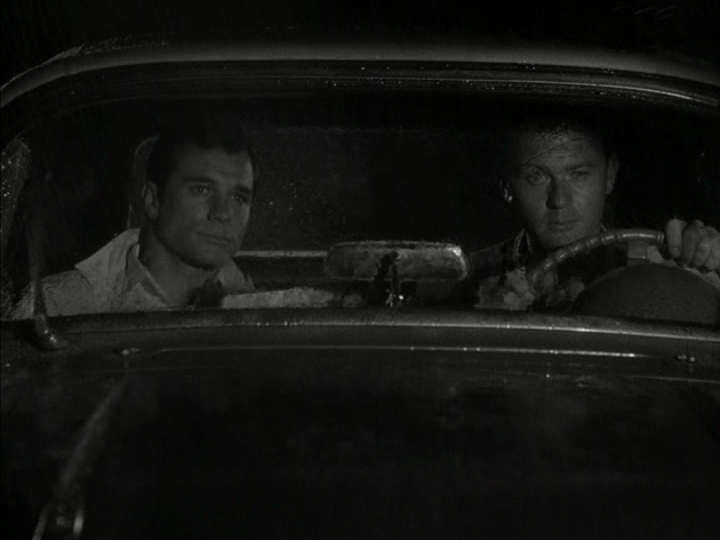

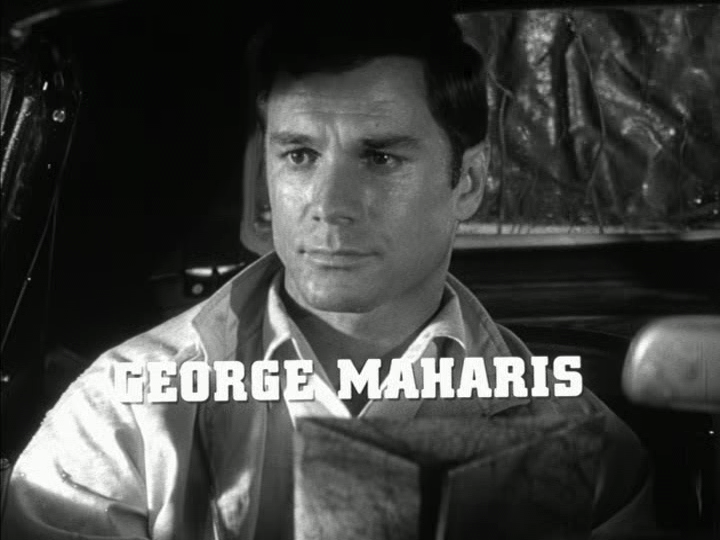

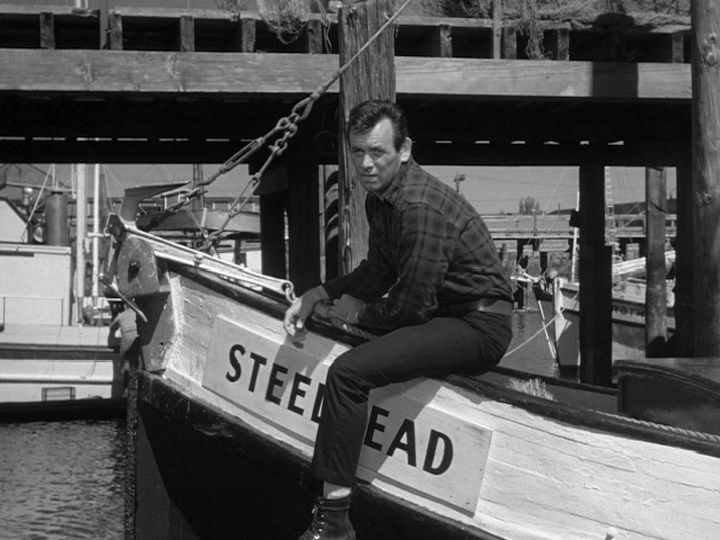

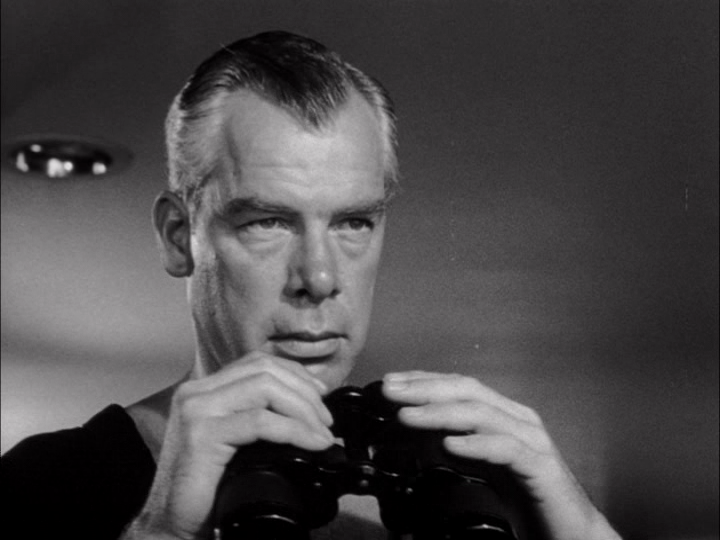

"We were able to show the American character on that show with all kinds of people in every kind of situation that gave us a special richness that would be difficult to show today since the country's become more homogenized. Regional differences are fading. There are more and more Holiday Inns and freeways." (1) ~ Co-creator and Head Writer Stirling Silliphant  The premise is irresistible: two young, idealistic guys, one sweet ride, a four-year road trip across early 1960s America. A new place every week, a new problem to face, new lives to encounter. Each episode of Route 66 would open in a fresh location, usually with an establishing shot of our two leads tooling down the road in their sleek Chevy Corvette, to the strains of Nelson Riddle's jaunty, jazzy theme tune, music that immediately conveys restless movement and the excitement of new discoveries awaiting around the next bend. For most of the series' four-year, 116-episode run on CBS, the two men in the Corvette's seats were solid, middle-class Tod Stiles (Martin Milner, later of Adam-12) and Buz Murdock (George Maharis), a working class tough from Hell's Kitchen with a poet's soul. When his wealthy father dies, Tod inherits his dad's Corvette, drops out of college and, together with best buddy Buz, hits the open road, on a voyage to discover America and maybe, along the way, themselves. The show was the brainchild of producer Herbert B. Leonard and writer Stirling Silliphant, who had earlier brought the edgy, humanistic cop drama Naked City to TV screens. (Silliphant also wrote the lion's share of Route 66's teleplays, along with Howard Rodman, whose authorial voice was sympatico with what Silliphant was trying to do.) The show was unique for a series made at that time (and for today, actually). The cast and crew would - much like the main characters - go on the road, arriving at a new location to much local fanfare, and film an episode or three there. Usually Silliphant, Rodman and the other writers would have traveled ahead, to soak up local color and atmosphere and to knock out scripts a few steps ahead of production. One of the many strengths of Route 66 is the appealing leads. Milner (29 years old when filming on the show began, and in real life married with several kids at the time) anchors the show as the rock-solid, slightly-square Tod, while the even older Maharis immediately commanded attention as the live wire, restless and emotive Buz. While Maharis proves to be the showier standout, Milner's presence is crucial, the glue that holds it all together, the yin to Maharis' yang. The casting was canny, as these two opposite types mesh extremely well, creating a believable, lived-in buddy relationship, two friends who might squabble from time to time but in the end always have each others' back, always try to keep the other out of trouble, always there to act as a sympathetic sounding board when the other one's in a jam.  Despite the charm and constant reassuring presence of the two leads, Route 66 was, in many respects, almost an anthology show. Each week, Tod and Buz encountered many lost, wayward or otherwise troubled souls, and did their level best to help or at least connect with them on some level. Sometimes, things worked out fine, and sometimes they didn't...but almost always, Tod and Buz had learned a little more about life along the way. Much like other TV series of the time, the roster of guest stars week in and week out was truly impressive, a mix of once-big stars on the way down the fame ladder, and burgeoning talent ready to rocket into the stratosphere. Some notable actors and actresses from both camps who appeared in the show include: James Caan, David Janssen, Lee Marvin, Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., Robert Duvall, Anne Francis, Julie Newmar, Dorothy Malone, Michael Rennie, Jack Lord, Suzanne Pleshette, Robert Redford, Nehemiah Persoff, Tuesday Weld, Martin Balsam, Janice Rule, Buster Keaton, Boris Karloff, Leslie Nielsen, Walter Matthau, Darren McGavin, George Kennedy, Lon Chaney, Jr., Charles McGraw, Inger Stevens, Jack Warden, DeForest Kelley, Sylvia Sydney, Ben Johnson, Royal Dano, Dan Duryea, Thomas Gomez, Lois Nettleton, Edward Asner, Nina Foch, Keenan Wynn, Beulah Bondi, Albert Salmi, John Ericson, Chloris Leachman, Ralph Meeker, Peter Graves, Arthur O'Connell...the list goes on and on and on. Aside from the great range of actors and actresses (as well as directors - Sam Peckinpah and Arthur Hiller helmed some episodes) who worked on Route 66, another aspect that fascinates today is the time-capsule travelogue element of the show. From Oklahoma to Oregon, from Pittsburgh to Louisiana, the show covered all manner of regions, ethnic enclaves, small towns and big cities. (In fact, the boys ended up driving their Corvette into plenty of places that were far off from the actual Route 66.) The cast and crew shot a lot of footage on actual locations, adding enormously to the show's production values. To keep gas in the tank and food in their bellies, Tod and Buz had to take whatever temporary work that came their way, and we get many scenes of them working on oil derricks, in factories and fields, on ranches and mills. There are also lots of scenes set at night, in seedy bars and swanky clubs, as the guys unwind and pursue romance, or tangle with shady underworld characters or assorted other losers, lowlifes and down-on-their-luck types. What the viewer is left with is a picture of an America that no longer exists - or, at least, is no longer quite as individual and ideosyncratic.

While ground-breaking and atmosphere-laden, the grueling shooting schedule required to put all these real locations and environments onscreen eventually took a serious toll on Maharis' health. The actor had graced the show with a a series of electrifying, charismatic performances, and it seemed he was destined for the big-time. There was a downside to the show that made him a star, however - the arduous schedule, the whole cast and crew working long hard hours to produce 30-plus one-hour episodes each year, mostly involving the lead actors doing the lion's share of their own stunts. The trouble started during the filming of the second season episode "Even Stones Have Eyes," when Maharis was forced to film several scenes in a freezing river, followed a few episodes later by him spending a good chunk of the episode "There I Am - There I Always Am" hip-deep in the freezing surf off Catalina Island. Maharis got sicker and sicker yet continued to work; he eventually contracted hepatitis from an injection given to him by a doctor brought in by the studio, and, when the producers wouldn't give him an adequate break to recover, was forced to walk off the set. During Maharis' convalescence, Tod went solo, the show's writers explaining away Buz's absence with a quick reference to him in a L.A. hospital recuperating from a virus, or having Tod call Buz near the beginning of an episode to touch base before heading on to his own adventure.  Producer Leonard was adamant that Maharis return to work promptly. After a mere 3 1/2 weeks off to recover in the hospital, Maharis came back for several episodes in the third season but it proved to be too much too soon, and before long the actor suffered from a relapse of the disease. It came down to a big decision for Maharis: continue with the show at the expense of his health, or walk away for good. His decision to leave the show possibly saved his life, but got him blackballed in Hollywood, and he ended up not working for the next 2 years. Several sources seem to agree that Maharis was treated shabbily by the producers, despite the fact that he had played a large part in making their show a success. Leonard hit Maharis with a breach-of-contract suit (settled out of court) and unceremoniously dumped Buz from the show; no further mention is made about him or his likely whereabouts for the rest of the series' run. Tod continued solo for a while longer until he got a new co-star, in the form of brooding Vietnam vet Lincoln "Linc" Case, played by Glenn Corbett. Unfortunately, the casting department failed to capture lightning in a bottle a second time: While a good actor, and possessing matinee idol good looks, Corbett was just a little too much like Milner: solid, straight-laced and likable, but lacking the fiery, passionate personality of his predecessor. An interesting factoid: apparently producer Leonard lobbied hard to get Burt Reynolds to take over from Maharis, but Reynolds reportedly wasn't interested in being another actor's replacement, and instead signed on to play blacksmith Quint Asper on Gunsmoke. When the show lost Maharis, it also lost that ineffable spark, the secret ingredient that made Route 66 special and work so well. The show managed to limp on for one more season and several quality episodes, but things just weren't the same, and it rode off the map after season four. Tod finally settles down, marrying Margo Tiffin (Barbara Eden), while Linc heads on back to Texas. According to Leonard: "We knew when George left the show it was over. But we had our audience and the network and sponsor renewed us for a fourth season with Marty and Glenn. Eventually though, the audience got bored with us, which was to be expected. It's sad when you think about the show's potential. The people at Chevrolet and I had been talking about taking Tod and Buz to Europe after the fourth season. Route 66 could have been the first American series shot abroad. After all, a year after we folded, I Spy actually accomplished that. I think, if George had stayed, we could have run for years." (3) (A mere sampling of Route 66's guest stars:)  Diane Baker Diane Baker Most fans understandably prefer the first 2 1/2 seasons with Buz and Tod together, but there are still several worthwhile episodes with Linc in the passenger seat. One of them, "The Cruelest Sea of All," features one of the series' occasional but unusual forays into the borderlines of fantasy and the supernatural. While Tod is working at the "mermaid show" at the Weeki Wachi Springs in Florida, he meets what seems to be an actual, in-the-flesh mermaid named Elissa (Diane Baker). They quickly fall for each other (Tod often falls for the comely female co-star of the week), but ultimately the pragmatic Tod is unable to make the leap into believing her story, and sadly, Baker bids him good-bye and leaps off the pier to disappear beneath the waves, ostensibly to return to her people under the sea. The episode closes on a bemused yet stubbornly skeptical Tod being gently chided by a philosophical Linc, who's not quite so sure that the girl wasn't indeed just what she said she was. The script by Silliphant is open-ended but seems to come down on Linc's side. An interesting and strangely haunting episode, unique in many ways but further proof of the wide range of story styles the show's format could handle. The freedom to shoot in so many disparate locations around the country also freed up the writers, and viewers each week could never quite be sure just what kind of story they'd be in for. While not frequent, Route 66 sometimes dipped into outright comedy, some ("Journey to Ninevah," with Buster Keaton and Joe E. Brown) more successful than others (the lame "Lizard Legs and Owlet's Wings," famous for the joint appearance of Boris Karloff, Lon Chaney, Jr. and Peter Lorre, playing themselves, but otherwise an inferior excuse for a Route 66 episode). There were also numerous mystery episodes, noirish suspense thrillers (even a few with a Gothic tinge) and other oddities that added spice to the general diet of thoughtful, human interest dramas.  Route 66 at times betrays its origins in those early, gritty social conscience dramas that graced legendary anthology shows like Playhouse 90: sometimes preachy, given to flights of poetic fancy, with literate albeit occasionally stagey dialogue that didn't really resemble the way people actually talk. Silliphant in particular specialized in heartfelt soliloquies that sometimes come across as so much pretentious purple prose (Silliphant also was enamored of arty, esoteric episode titles, such as "A Fury Slinging Flame," "From an Enchantress Fleeing," "Narcissus on an Old Red Fire Engine," "Poor Little Kangaroo Rat," or "How Much a Pound is Albatross?") But the show remains unique in its characters' constant grappling to articulate their inner turmoils, longings, regrets and fears. It's this struggle to embrace and express truths and honestly confront a wide range of complex emotions that sells the occasional artifice of speechifying the writers indulge in. And just when the existential angst threatens to become too much, the program throws in a fight scene, a spot of surprising action or melodrama, a playful romance or a bit of lighthearted horseplay between Tod and Buz. The end result is a TV show that - while occasionally heavy-going or even at times downright depressing - feels more adult, literary and full of bleeding, bruised heart than the norm. Ultimately, Route 66 was a program legitimately trying to talk about complicated, real-world, adult issues as honestly as was possible in an early 60s commercial TV environment, without resorting to pat answers or a tidy wrap-up, and more times than not, succeeded. Route 66 is a series I came to late. It may have aired in my local TV market (the Pacific Northwest) but if so I don't remember it amongst all the other classic TV shows that peppered the syndicated airwaves back when I was growing up. The show enjoyed a good run on Nick at Nite during the 80s, which also passed me by. My first exposure was via Infinity / Roxbury Entertainment's Season One DVD set from several years ago. I bought the first volume and was immediately impressed with the program's freewheeling format, location photography, generally excellent writing, engaging stories and likeable main characters. I think it's easily one of the great TV series, and deserves to be better known. Hopefully, exposure to new audiences on Me-TV will garner it new fans, and not allow it to join the rapidly-growing graveyard of forgotten TV gems of years past. I have yet to see all of the episodes (especially from season four), but so far, some of my personal favorites include: * "The Man on the Monkey Board," in which Tod and Buz, while working on an offshore oil rig in the Gulf off Louisiana, meet a man (Lew Ayres) on the hunt for a Nazi war criminal hiding out amongst the workers. * "Ten Drops of Water," which finds the boys in Utah helping a poor family on a rundown desert ranch, struggling to get enough water to maintain their livestock during a long drought. * "Layout at Glen Canyon," where Tod and Buz get involved with a group of models on a photo shoot while the Glen Canyon Dam is still under construction (this episode climaxes with an incredible scene of the lead actors running through a series of actual explosions; I'd never seen its like on a TV show before.) * "Fly Away Home," a two-parter filmed near Phoenix, Arizona, featuring Michael Rennie as a guilt-wracked cropduster pilot and Dorothy Malone as his estranged wife. * "An Absence of Tears," an interesting noir where the guys aid a blind woman (Martha Hyer) trying to track down her husband's killer. * "Welcome to Amity" - Amity, Ohio, that is - where Tod and Buz encounter a troubled young woman (Susan Oliver) towing a headstone behind her car.  * "First-Class Mouliak," where the guys get involved in the inter-family strife of a group of Polish foundry workers. * "The Mud Nest," a more personal story for Buz, as a detour to a remote town puts him on the track of a woman who might be his mother. * "There I Am - There I Always Am," an increasingly intense episode set on a nearly-deserted Catalina Island, in which Buz tries to rescue a woman (Joanna Moore) whose foot is pinned between two rocks as the tide comes inexorably in... * "One Tiger to a Hill" finds Tod and Buz clashing with a surly, disturbed war veteran (David Janssen) while working on a salmon fishing boat in Astoria, Oregon. A final note about the unofficial third co-star of Route 66 - the Corvette. According to Sam Manners, "Every 3,000 miles, we would turn in the Corvettes we used on the show and get new ones. We probably went through 3 - 4 cars each season." (4) Seasoned car aficionados will doubtless spot when Tod's car changes over to each new year's model. There's no denying, though, that the boys traveled in style. This post is part of Me-TV's Summer of Classic TV Blogathon hosted by the Classic TV Blog Association. Go to http://classic-tv-blog-assoc.blogspot.com) to view more posts in this blogathon. You can also go to http://metvnetwork.com to learn more about Me-TV and view its summer line-up of classic TV shows. DVD Note: Route 66: The Complete Series is available from Shout Factory. All screencaps above taken from the earlier Infinity / Roxbury Entertainment releases (I understand the Shout set likely utilized the same masters for seasons 1-3.) The Roxbury sets were initially plagued by problems, such as the occasional dull, murky transfers mixed in with near-pristine ones, but to the company's credit, most of these problems were corrected with re-released sets. Shout has also done consumers the kindness of releasing the orphaned Season 4 in its own stand-alone set. Now, most of the episodes are complete and uncut ("A Fury Slinging Flame" sadly remains an abbreviated syndication print) and boast nice-looking transfers. I'm just happy to have this terrific series complete in my home video library. Source Note: (1) - (4) excerpted from Route 66: The Television Series, by James Rosin, published by the Autumn Road Company, 2011.

30 Comments

|

Talking about all sorts of television, especially the good old stuff...

Hey!!! Be sure to subscribe to the RSS feed below, to be informed of new postings! Neat-O Keen-O TV Blogs

Double O Section

From the Archive (a British Television Blog) The Classic TV History Blog (Stephen Bowie's site) The Stupendously, Amazingly Cool World of Old TV TARDIS Eridutorum Cathode Ray Tube Other Cool TV Sites

Archives

November 2015

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed