The Stalking Moon

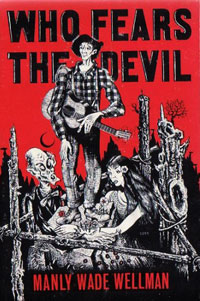

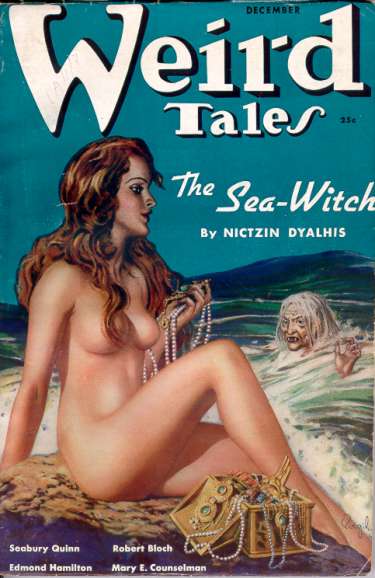

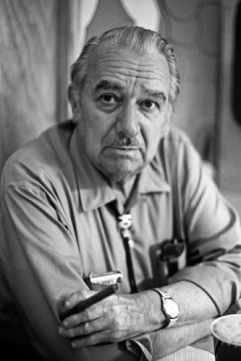

I remember my first encounter, nearly 30 years ago, with the wonderful, weird fiction of Manly Wade Wellman. I was browsing the shelves of my local library when I came across a copy of The Old Gods Waken. Intrigued by the cover and the synopsis, I took the book home and was instantly captivated by its story of a folksy hero named John, whose pure heart and silver-stringed guitar help him defeat a couple of modern day druids up to no good in the remote Appalachian mountains. Wellman felt like some sort of a private little discovery to me, and from then on, I tried to get my hands on nearly anything else written by him I could find...not always an easy task. Manly Wade Wellman may be one of the very best writers of dark fantasy fiction that hardly anyone knows about. Over five decades, he wrote dozens of novels and stories of all types, but he especially excelled at the weird horror story, particularly those of the "supernatural investigator" variety. As a young man, he earned his stripes writing for pulp magazines like Astounding Stories, Unknown, and, most memorably, Weird Tales, where he first introduced his erudite, monster-hunting men of action, Judge Keith Hilary Pursuivant and John Thunstone. Most of Wellman's fame arises from the cycle of stories published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in the 50s to early 60s, featuring a wandering, amiable guitar-strumming fellow named John. Those 11 original "Silver John" stories were eventually published in the collection Who Fears the Devil? by Arkham House in 1963. (Wellman was never fond of the "Silver John" nickname, a publisher's idea, and never used it himself in any of his stories featuring the character.) These early Silver John stories are beautifully crafted pieces of work, all featuring a clear, strong narrative voice, a terrific sense of place, and above all, a cohesive and original take on mountain culture and homegrown legend, complete with plentiful details of the food, living conditions and folk songs of the region. Wellman lived most of his later life in North Carolina and made a deep study of the region. This knowledge lent conviction and authority to his many eerie tales of the monster and magic-haunted backwoods of Appalachia. It's hard to describe what makes Wellman's stories so special. It's a subtle flavor, really. His work is seldom scary in the traditional sense; it's more that he creates an extremely effective sense of unease, of strange, evil entities, lurking just out of the range of one's vision, haunting the isolated, dark forest trails of the Appalachian mountains. In an almost offhanded way, he created a unique mythology, peopled by voluptuously beautiful, wicked witches, sneering, disdainful warlocks, Native American legends, ancient races inimical to humans (such as the Shonokins), and all manner of creepy critters like the Flat, the Gardinel, the Behinder, and the Dakwa. While Wellman is very, very different in prose style from that other American master of the supernatural, H.P. Lovecraft, the two share a talent for vivid, carefully-constructed world building, giving their otherworldly manifestations a rare authenticity through cumulative effects, such as the use of fictional tomes of black (and white) magic. Lovecraft's The Necronomicon is the more well-known, but just as effective is Wellman's book of simple evil-thwarting spells, The Long Lost Friend, used across several stories and multiple series.  When fellow fantasist and fan, Karl Edward Wagner, edited Worse Things Waiting, published by Carcosa Press in 1973, the collection went on to win Wellman a World Fantasy Award, and the author enjoyed a well-deserved career resurgence which lasted until his death in 1986. A whole new passel of influential fans commissioned new works, and Wellman eventually returned to his most popular creation, penning a handful of new Silver John stories. He eventually went on to produce five more John novels for the Doubleday Science Fiction imprint, starting with The Old Gods Waken (1979), After Dark (1980), The Lost and the Lurking (1981), The Hanging Stones (1982) and The Voice of the Mountain (1984). The novels, it must be said, all suffer from some definite padding and the occasional repetitive conversation, and lack the control, sharp through-line and lean beauty of the early Silver John short stories. Despite this, the novels all have points of interest, particularly the chance to spend more time in the pleasant, garrulous company of John, who one can easily imagine sitting on the porch outside some old-timey country store, relating his adventures to a wide-eyed audience. While The Old Gods Waken remains, for me, the best of the bunch, The Hanging Stones is still an engaging read, thanks to its inspired premise and the brief but welcome presence of Wellman's first supernatural investigator, Judge Pursuivant. This meeting of two of Wellman's legendary creations enlivens the second half of book; the first half, it must be said, is a little too much talk, and not a lot of action. The paperback synopsis reads: "Millionaire industrialist Noel Kottler had no respect for mountain lore. He wanted to build a duplicate of Stonehenge high on top of Teatray Mountain, turn it into an amusement park, and hire Silver John to entertain the tourists. But the sharptoothed wolf demons who dwelt in the back-country were angered by the invasion of their sacred ground. And Silver John had no use for money-mongers and citified mystics. When his beloved Evadare was kidnapped and unholy darkness was unleashed upon the land, only the pure-hearted power of Silver John could restore the sunshine and subdue the savage spirits." If the above plot description doesn't sound busy enough, the book also features the ancient spirits who built the original Stonehenge, summoned back to violent life by a mysterious stranger named Esdras Hogue, to ultimately devastating effect. All these elements would make for a crackerjack 50 - 70 page novella, but the impact is somewhat dulled due to being stretched out to novel length. Nevertheless, once John's lovely wife Evadare is taken captive by the brutish werewolf folk who claim Teatray mountain as their own, John's lackadaisical narrative takes on a much-needed urgency and the last 50 or so pages barrel along nicely, ending in a fiery, mystical climax. That's not to say that there isn't some typically evocative writing earlier on in the book. Take this passage, for instance, as John goes poking around the dark woods where the wolf-like men dwell, and chances across an old, run-down church: "It was made out of planks, I said, sawed out of big trees sometime in the past, and now turned all gray with crumbly black veins for want of a coat of paint since God alone could remember when. Two windows in front, one on each side of the cleated board door, and their glass all broken in and jaggly-looking. On the gabled roof of shakes, a little steeple thing, though it had nair been big enough to have a bell in it. On the door itself was a bald place where once two slats had been nailed to make a cross, the cross now fallen off from it. Over the walls scrambled vines and patches of gray-green lichen. I tell you for a natural fact, it was lonely and empty, and I felt lonely and empty to look at it. I stood there and looked, and thought my thoughts. Then it was that the door caved open, slow and creaky on red-rusted hinges. It opened inward, though no hand was on it, and I could see into the dark inside where there were rickety benches with no backs to them - benches home-carpentered of more whip-sawed planks, set up on round chunks of poles. At the far end, where things were the gloomiest, a little low-set platform and a reading desk, where once a preacher could make him a pulpit of it. The opening door showed me those things, and it seemed like as if it bade me to come in. But you can bet your neck I didn't do that thing."  Atmospheric stuff, ain't it? Despite its leisurely pace, the high quality of the writing, and John's easy-going, countrified yet elegant narration, keep the reader turning the pages until the exciting finale. And despite the coziness lent by the presence of its multiple heroes, the novel ends on a chilling final image of death. Wellman was hale and hearty into his early 80s, but when he sustained a serious fall in 1985 which rendered him an invalid, this proud, strongly-built man's health rapidly deteriorated, and he died the following year. He managed to produce one more novel, Cahena, a historical adventure, before his death, and it was published in 1986. By now a close friend of Manly and his wife, Frances, Karl Edward Wagner edited a new collection of miscellaneous Appalachian fantasy stories also released by Doubleday, The Valley So Low, in 1987. For those new to Wellman, I'd suggest leaving late-period novels like The Hanging Stones until later, and instead seek out his earlier short masterpieces, such as "O Ugly Bird," "One Other," "Old Devlins Was A-Waiting," "Toad's Foot," "Hundred Years Gone," "Yare" and "The Dakwa," to name but a very few. All the Silver John short stories can be found in the paperback John the Balladeer (1988, also edited by Karl Edward Wagner). In the early 2000s, Nightshade Books published 5 handsome hardback volumes, collecting pretty much all of Wellman's fantasy short stories and novellas, including a volume of all the Silver John stories, Owls Hoot in the Daytime and Other Omens. Sadly, all but one of these collections seem to be out of print and going for big bucks on Amazon Marketplace, but are well worth getting if you can find them cheaper elsewhere. There was also a nice hardback collection of all the John Thunstone stories, including the two later novels What Dreams May Come and The School of Darkness, put out by Heffner Press in 2012, and now going for outrageous prices.

If you're a fan of this kind of literature, I'd say get a hold of some of these editions by any means necessary. If and when you are lucky enough to do so, I wouldn't be surprised if you, too, became a Wellman fan for life. My Rating: The Hanging Stones: B All the stories in Who Fears the Devil, plus many of his other short works: A+++

3 Comments

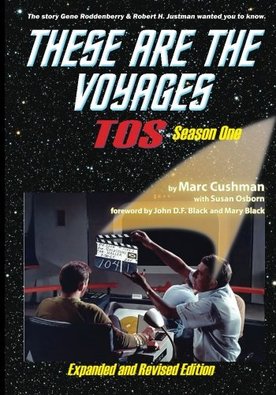

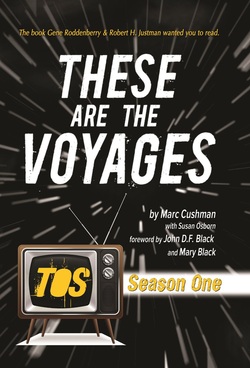

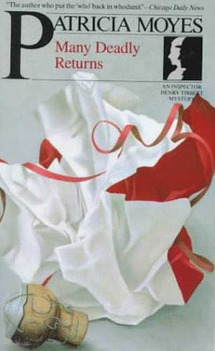

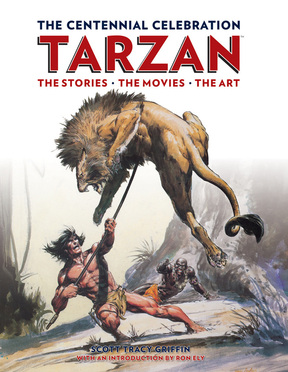

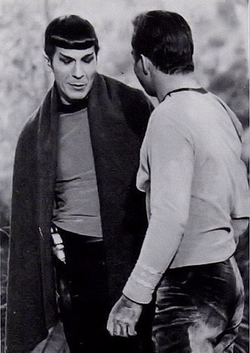

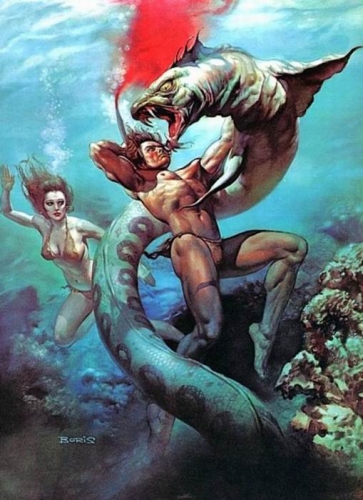

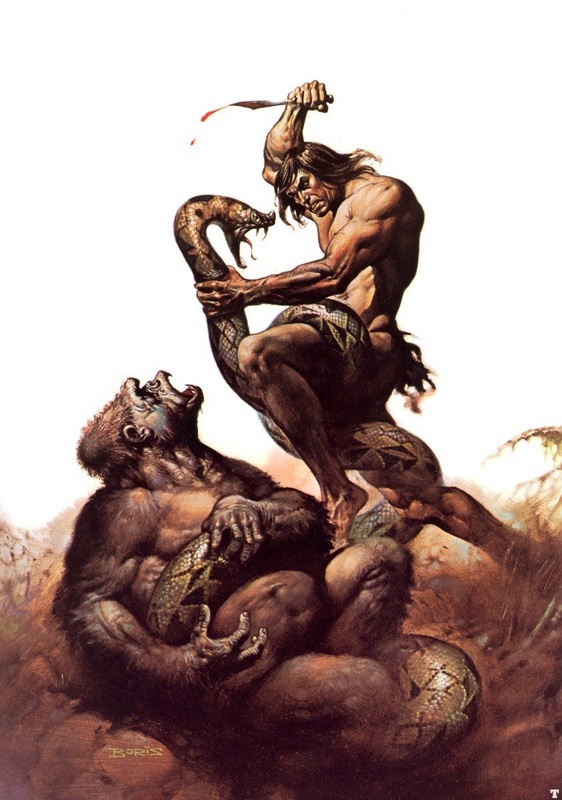

Be sure to get this revised edition... Be sure to get this revised edition... Look...I know what you're thinking. "What...another book about Star Trek? Don't we have enough of those things already?" Trust me... there's never been a book about Star Trek like this one. Marc Cushman has pretty much put out the last word on the subject of the making of Star Trek: The Original Series (TOS for short) with this exhaustively researched, yet lively and endlessly fascinating volume. Several years ago, Cushman (with co-writer Linda J. La Rosa) wrote I Spy: A History and Episode Guide to the Groundbreaking Television Series - easily one of the best books of its type. That book, detailed as it was, covered all three seasons of I Spy. Cushman does the same thing here with Star Trek, only writ large. He's given each season of classic Trek a whole 600 plus page book. Getting to know Gene Roddenberry near the end of his life, along with production manager Robert Justman, Cushmas gained access to somewhere between 60 to 70 boxes of correspondence, inter-office memos and other paperwork produced during the production phase of the show, and has culled a wealth of never before seen, behind-the-scenes details about the making of this iconic science fiction TV series. After a lengthy prologue delineating the trials and tribulations of making the show's original, rejected pilot, "The Cage," and the long process of getting the series on the air, the remainder of the book is generally organized into chapters dedicated to each episode of the first season, broken down into separate sections, starting with a plot synopsis (courtesy of the original NBC press release), with additional comments from Cushman; then "Sound Bites," which includes some pithy quotes from the episode; then "Assessment," a mini-essay with the author's own critical take on the episode. Then the real research kicks in, with "The Story Behind the Story," which includes highly detailed, blow-by-blow analysis of the scripting process through to finished, ready-to-air product, covered in separate sections labelled "Script Timeline," "Pre-Production," "Production Diary," and "Post Production," all of these liberally sprinkled with quotes from most of the people involved. He then finishes up with sections titled "Release/ Reaction," which covers the ratings situation for that given episode against its nightly prime-time competition; a "From the Mailbag" snippet which includes fan letters to the show's producers; and "Memories," which features final comments from the the various actors, crew and writing staff involved with that episode. (To check out some lengthy excerpts from Volumes One and Two, head over to the writer's dedicated website here.) Simply put, this is great stuff. Some interesting revelations come to light in the book, including Cushman's debunking of the long-accepted myth that Star Trek fared poorly in the ratings. The author provides data proving that - for the first season, at least - this is just not true. TOS actually did very well in the ratings, competing head to head with juggernaut hit Bewitched and usually coming in a close second, and on more than one occasion, winning its time slot.  ...and not this earlier version. ...and not this earlier version. Another thing that becomes abundantly clear while going through this book is just how much of a total bitch this program was to put together. How it ever got made and on the air in the first place verges on the miraculous. From the massively-detailed look at the process of commissioning scripts (many from established sci-fi authors who, though talented in their own field, knew virtually nothing of the strictures and specialties of writing for television), trying to get the scripts into workable shape, with many hands (including Roddenberry, Gene L. Coon and others) re-writing and polishing them many times over, to getting the stories passed by the studio's censors and executives, to the travails of the physical production, wrangling the actors, props, make-up, costumes and set designers to complete shooting within the restrictions of budget and a 6 to 7 day schedule - the work involved was enormous and constantly challenging. Not to mention the nightmare of perpetual delays in getting workable special effects from the multiple F/X houses scrambling desperately to keep up with the production and editing schedule, as well as all the other myriad problems that typically plagued a TV production at the time...really, it's incredible that the series ever lasted beyond the first half of its inaugural season. All in all, I can't recommend this book highly enough - for fans of Star Trek, or television science fiction in general. At all times, Cushman never loses sight of making this a fun read, keeping the masses of detail interesting and including lots of great quotes, anecdotes and observations from all the key players behind and in front of the camera. Really, this is the neo plus ultra of all Star Trek books. I can't wait to get my hands on Volume 2 - available on Amazon now. My Grade: A + A few images found in the book, courtesy of http://www.thesearethevoyagesbooks.com/  In all the years that I've been a fan of detective fiction - British crime fiction in particular - the works of Patricia Moyes have floated around the periphery of my reading in the genre, occasionally stirring my interest. However, it wasn't until recently that I actually sat down and read one. Many Deadly Returns (published in the U.K. as Who Saw Her Die?), is the ninth of 19 novels Moyes wrote, between 1959's Dead Men Don't Ski and 1993's Twice in a Blue Moon, featuring the mild-mannered yet shrewd Inspector Henry Tibbett and his perceptive wife, Emmy. And a very enjoyable mystery it is, with an intriguing set-up and a cleverly worked out, fairly clued plot. The blurb on the back cover lays out the scenario nicely: "Lady Balaclava, an eccentric socialite with a huge fortune, is about to celebrate her birthday. When her Ouija board warns of danger, she takes a special precaution: Chief Superintendent Henry Tibbett and his wife are asked to attend. The now elderly Lady Crystal Balaclava was quite a woman-about-town back in her heyday, and has many influential friends. The assistant commissioner of Scotland Yard tasks Tibbett to surreptitiously keep an eye on things. Tibbett reluctantly agrees to head out to Foxes' Trot, Lady Balaclava's aging eyesore of an estate, on what he thinks is a fool's errand...but his detective "Spidey sense" start tingling once he meets Crystal, her bluff, longtime companion, Dolly Underwood-Threep, and Crystal's three daughters, who've all assembled for her annual birthday celebrations. Lady Balaclava proves to be full of surface charm but is a bit of a scheming minx, and her youngest daughter Daffodil ("Daffy" for short), married to rich American tycoon Charles Z. Swarsheimer, is cut from the same cloth. Middle daughter Violet lives in working-class surroundings in Holland with her husband, Piet van der Hoven, who grows first-class roses. Oldest daughter Primrose has settled in Geneva and is married to an eminent Swiss doctor, Edouard Duval. Lady Balaclava's long-dead husband had carefully planned out his will, ensuring that none of the daughters would inherit anything until the death of their mother, and further, that their husbands have no legal way of laying a finger on the money themselves.  So when Lady Crystal drops dead on her birthday in front of everyone, Tibbett is certain she was poisoned. But who did it - and how it was done - prove fiendishly difficult to suss out. For one, motives seem thin on the ground, especially when the likeliest suspect, old pal Dolly, who, seemingly much to her surprise - and the daughters' annoyance - inherits the house, jewelry and a handsome 50,000 pounds, is poisoned as well. Dolly isn't killed, merely hospitalized...which begs the question - was she a victim, or is she playing an even deadlier game? With his storied professional reputation at stake, Tibbett takes a leave of absence to get to the bottom of the case and unmask a ruthless, cunning killer... Moyes writes smoothly and with a good deal of quiet, observational wit, and this ends up being an intelligent take on the classic "country house" style of murder mystery, albeit in a more modern setting and with a good deal of location hopping, as Henry and Emmy travel to London, Holland and Switzerland during the course of their investigations. While the Balaclava offspring and their mates remain aloof and mostly unlikeable, it's more than made up for by the vivid characterization of Dolly - one of those wonderfully phlegmatic, redoubtable eccentrics that frequently populate British crime fiction. And, of course, Tibbett and Emmy are charming, if low-key, company. Overall, this is a solid mystery novel that delivers the goods, served up with panache - not as richly drawn and colorful as a Margery Allingham or Gladys Mitchell yarn, perhaps, but definitely worth the time for detective story addicts. My grade: B + Tarzan: The Centennial Celebration - The Stories, The Movies, The Art (2012) by Scott Tracy Griffin1/29/2014  In 1912, Edgar Rice Burroughs debuted his most famous creation in his second-ever novel, Tarzan of the Apes, and changed not only his life, but popular culture, forever after. For decades, the Lord of the Jungle dominated the fictional landscape, in every medium imaginable. A hundred years later, times might have changed and audiences become more cynical, yet Tarzan's legacy, his hold on the public's imagination, though somewhat dimmed from its once-majestic peak, still echoes on. Adaptations still keep coming, including an animated Disney TV series, a stage production and a theatrical animated film, all in the past 12 years. A century is a long time for a fictional character to still hold currency, and dedicated Burroughs scholar Scott Tracy Griffin's Tarzan: The Centennial Celebration commemorates this impressive span in style. I usually don't go in for coffee table books. Always heavy on beautiful imagery but light on actual content, the typical coffee table book is fun for a quick perusal but rarely commands repeated attention...something you pick up once or twice and then rarely look at again. Happily, Griffin's terrific compendium is a notable exception. In short, it is - like its subject - magnificent. Published by Titan Books, Tarzan: The Centennial Collection is huge (13 x 10 inches) and beautifully designed, with thick, glossy pages chock full of stunning images, but Griffin hasn't scrimped on the text side of the equation, either. This a fabulous, juicy tome that not only is a feast for the eye and a salve for the soul of adventure fiction junkies everywhere, but works as a splendid overview of Burroughs' most famous character.  Neal Adams cover art for TARZAN OF THE APES Neal Adams cover art for TARZAN OF THE APES More than half of the book's 320 pages are dedicated to what started the phenomenon in the first place - Burroughs' novels: several pages for each Tarzan title, including a non-spoilery plot synopsis, plus several paragraphs providing background details about their writing, including notes on the author's research methods, word count (most of the novels seem to average 75,000 to 80,000 words), payment for each story, the sometimes quite involved back-and-forth negotiations on their publication, etc. Coverage of each novel is of course accompanied by numerous (and wonderful) cover paintings, from the original hardback dust jackets by J. Allen St. John to 1960s Gold Key comic art by George Wilson. The real highlights are the plethora of cover plates from the various Ace, Dell and Ballantine paperback runs from the 60s and 70s, especially focusing on the work of Robert Abbott, Neal Adams and Boris Vallejo, often gifted with a whole page each, the better to study their artistry in greater depth. Griffin also peppers the book with sidebar articles (equally lavishly illustrated) on all manner of Tarzan-related goodies, from entries on Jane, the various beasts of Tazan (Tantor the Elephant, Numa the Lion, Nkima vs. Cheeta, etc.), Korak (Tarzan's son), Pellucidar, feral children, lost worlds, implacable foes, femmes fatales, an "ape language" glossary, and on and on. Later chapters of the book delve into Tarzan's forays into the world of comics (both newspaper strips and comic books), radio, film, television, stage, memorabilia and the like. Every possible facet is covered in brief, with myriad nuggets of information that many fans might not be aware of. (For example, did you know that actor Rod Taylor of The Time Machine fame starred in over 800 15-minute Tarzan serials for Australian radio in the late 50s? I sure as heck didn't!) There are also a couple of fascinating biographical chapters (again, accompanied by rare and enlightening photographs) discussing Burroughs youthful military service and later life as a world famous, elder statesman writer hanging out at his Tarzana ranch (and, of course, Tarzana itself gets its own chapter).  Art by Robbert Abbott Art by Robbert Abbott Author Griffin definitely knows his stuff, and really, for a One Stop Shopping trip to the savage, mythical lands of the Lord of the Apes, you could hardly do better. I've found myself breaking the coffee table book curse and returning to the book every day over the past several weeks since I first got my hot little hands on it, pouring over the incredible artwork, gleaning new-to-me details from the text - basically, savoring each individual section like a delicious ice cream cone. And best of all, the book has inspired me to start working my way through those original Tarzan novels, many of which I've never got around to reading before. Indispensable for fans of Tarzan, Edgar Rice Burroughs, pulp adventure fiction, and wonderful cover art in general, and worth much more than what it's currently going for on Amazon (can you tell I like this thing?), Tarzan: The Centennial Celebration comes highly, highly recommended. My Grade: A+ Above, typically evocative cover art by Boris Vallejo, for TARZAN AND THE FORBIDDEN CITY (left) and TARZAN, LORD OF THE JUNGLE.

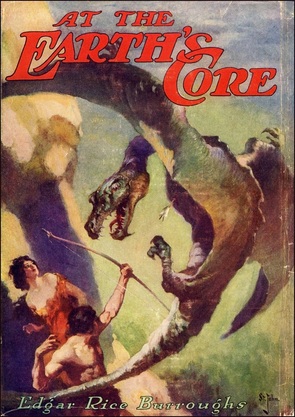

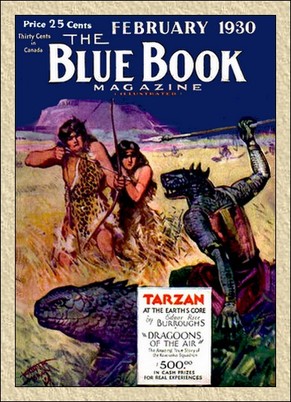

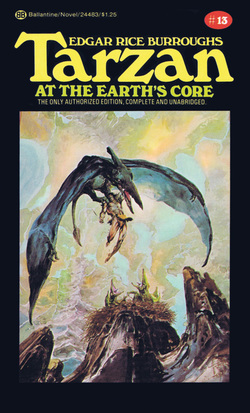

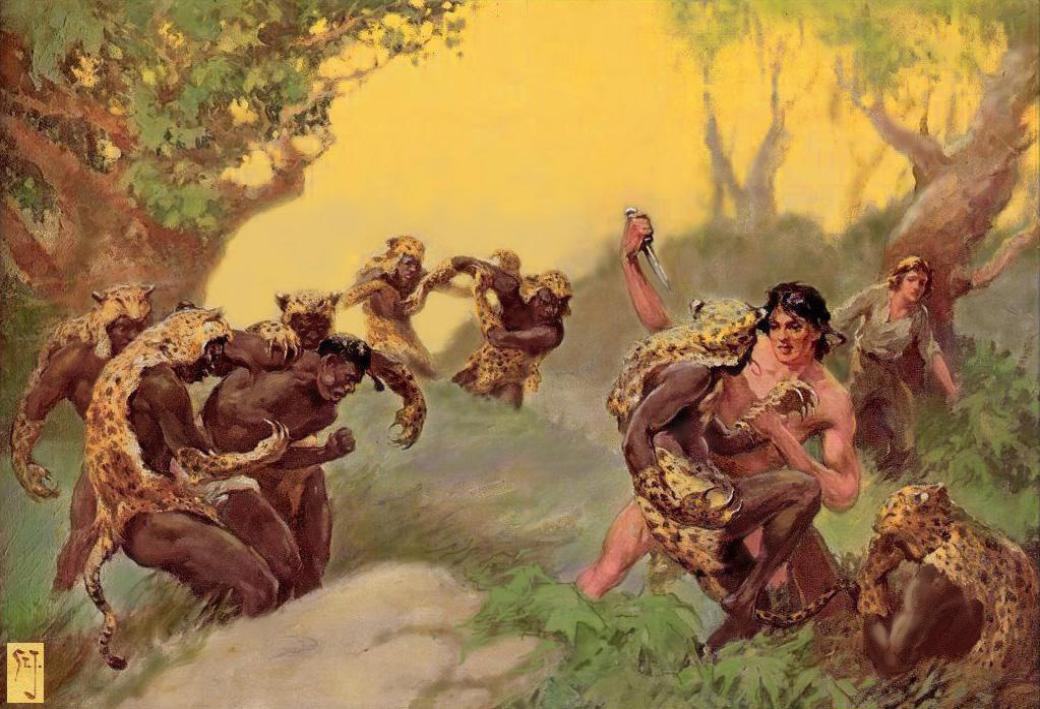

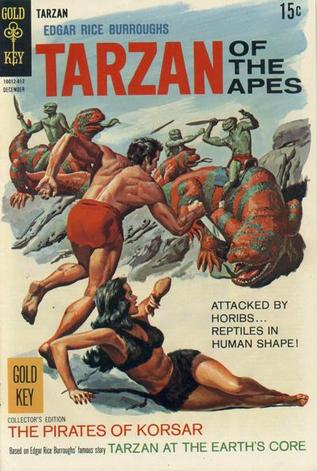

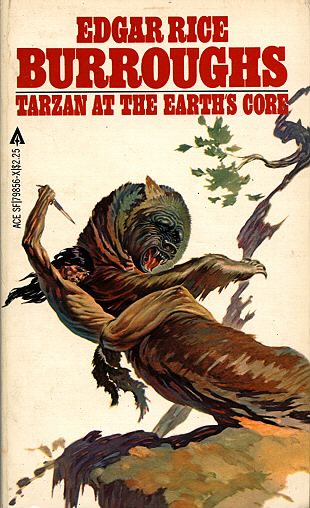

Pulp giant Edgar Rice Burroughs has seemingly never been out of print, despite his earliest books being 100 years old. Thanks to the paperback reprint boom of the 60s and 70s, I grew up devouring his exciting tales of incredible adventures, lost worlds full of monsters, manly heroes, dastardly villains and proud, regal heroines. Burroughs saw enormous success in his career and influenced countless other writers who followed him. His most famous creation was of course Tarzan, orphaned son of British missionary parents who died in Africa, leaving him to be raised by apes, overcoming assorted deadly challenges to eventually become Lord of the Jungle, all chronicled in Burroughs' second-ever book, Tarzan of the Apes, in 1912. While Tarzan became a wildly popular, iconic character, spawning 23 novels, a final story collection (Tarzan and the Castaways) and a collection of stories for young readers (Tarzan and the Tarzan Twins), I tended to gravitate to Burroughs' other, more fantastical works in my youth. Perhaps my relative disinterest was due to the sheer fame of the Tarzan brand, especially the proliferation of Tarzan movies (none of which, entertaining as many of them are, have ever truly captured the essence of the literary Ape Man; you'll find none of that monosyllabic Weissmuller "Me Tarzan, you Jane" tripe in the books, for starters). I liked the Tarzan books well enough, and read several, but generally preferred things like Burroughs' John Carter / Barsoom series; his trilogy about the Land that Time Forgot, Caprona; and such one-offs as the Prisoner of Zenda-inspired The Mad King or The Cave Girl. But most of all, I was taken by his series of novels about that strange world at the center of the Earth, evocatively named Pellucidar - that savage land of misty jungles, rolling savannah and mighty inner seas, teeming with prehistoric beasts, primitive men and all manner of weird, humanoid races. So it's no surprise that the one Tarzan novel that really fired my youthful imagination was the one where these two series cross over - Tarzan at the Earth's Core.  Originally published in serialized form in The Blue Book Magazine from September 1929 to March 1930, Tarzan at the Earth's Core, book #13, comes right smack in the middle of the character's lengthy run, one of a handful of inspired mid-series' gems that are among its most memorable and show off their author's inventiveness and storytelling verve to great effect. Book 8, Tarzan the Terrible, finds Tarzan in the lost world of Pal-U-Dan, where he first encounters dinosaurs, the carnivorous, triceratops-like Gryfs. The tenth book in the series, Tarzan and the Ant-Men, finds our protagonist in yet another lost world, Minunia, peopled by a miniature race of humans a quarter of normal size. This novel is followed by the less fantasty-oriented but still highly imaginative Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle, which finds the Ape Man contending with jousting tournaments and court intrigue alongside descendants of European Knights Templar in (you guessed it) another isolated lost region, this time a "forbidden valley" in the mountains. This burst of creative world building that flowered in these mid-pack Tarzan entries reaches its apex in the splendidly colorful and action-packed Tarzan at the Earth's Core.  Pellucidar was already a well-established world by the time Tarzan at the Earth's Core came out. Burroughs had already published three volumes in the 7-book series, starting with At the Earth's Core in 1914. A sequel, Pellucidar, immediately followed in 1915. Then, for some reason, Burroughs interest in his "inner world" playground flagged, and it wasn't until 1929 that he returned to it, with two books in quick succession, Tanar of Pellucidar and this Tarzan crossover. Pellucidar ends in a cliffhanger, with hero David Innes imprisoned by the piratical, seafaring Korsars, and Tarzan at the Earth's Core begins with Innes' American friend, Jason Gridley, leading a mostly German expedition to Pellucidar to rescue him. But first, Gridley travels to Africa to enlist the aid of Tarzan, and soon that worthy is on board the huge airship, the 0-220 (described in loving detail at the end of Chapter 1), captained by Herr Zuppner, as the massive dirigible descends slowly into a polar opening into the subterranean world. No sooner does the 0-220 touch down upon the grassy plains of Pellucidar than Tarzan is off exploring, his finely-attuned senses exulting in a wilderness virtually untouched by modern man. From there on out, it's one wild escapade after another, as Tarzan gets separated from the rest of the crew, is captured by the ape-like humanoids, the Sagoths, befriends one of them, and escapes. Meanwhile, Jason Gridley also ends up on his own in this hostile land, and goes through a concurrent series of adventures, mostly in the company of a beautiful primitive maiden, Ja, the Red Flower of Zoram. The novel follows both Tarzan and Jason, as they struggle with the myriad creatures and warring races of Pellucidar, with only a few brief cutaways to the desperately-searching 0-220 crew. While Burroughs' prose might not be of the caliber of that other pulp king, Robert E. Howard, he didn't achieve his lasting popularity without good reason. The man was a master storyteller with a prodigious, seemingly endless imagination, and Tarzan at the Earth's Core is great, escapist reading all the way. He even manages to pull off a fairly interesting romance between Jason and cave covergirl Ja, amidst all the peril, rampaging Snake Men, pterodactyl attacks and other mayhem. I suppose it should go without saying, but I'll go ahead and state it anyway: like most pulp novels, Tarzan at the Earth's Core reflects its times, and many readers may find some of the casual racism eyebrow-raising. While Burroughs treats his heroic German characters with respect (written as this was between the two world wars), he also tosses in a stereotypical Stepin Fetchit-style black cook for supposed comedic effect, complete with phonetically-rendered dialect ("Lawd! You all suah done overslep' yo'sef.") These moments are few, however, and mainly contained in the first few chapters, and Burroughs does contrast the Robert Jones character with Tarzan's handpicked squad of proud, courageous Waziri warriors. That said, those willing to look past these bits, and whose tastes run to old-fashioned pulp thrills and high adventure, will find much to savor here. I first encountered and fell in love with this novel as an 11-year-old (the perfect age), in the 60's Ballantine Books paperback version with the Neal Adams cover (pictured above left), but there have been many other nice copies published over the years, including a Dell comics version. I still get a kick out of the book to this day, and every five years or so, pull it off the shelf and am instantly cast back to my teenage days, running alongside Tarzan and his friends, battling dinosaurs, beastmen and other terrible dangers in the hot, humid jungles and grassy plains of Pellucidar. My Rating: A A Gent From Bear Creek (1937) - The Breckenridge Elkins Western Stories of Robert E. Howard9/2/2013  I've long been an admirer and reader of the excellent pulp fiction of Robert E. Howard, but his western stories are a recent discovery for me. Howard (1906 - 1936) of course is most famous for being the creator of Conan the Barbarian, Kull the Conqueror and Puritan monster slayer Solomon Kane, but he was adept (and prolific) at nearly every kind of adventure fiction genre imaginable. From his best known tales of sword-and-sorcery, planetary romance, and Lovecraftian horror, to boxing stories, sailor stories, "spicy" pulp heavy-breathers, historical tales of pirates and desert sheiks, "true detective" stories and private detective and cowboy yarns, there was nary a genre left untouched in his short but prodigious career. Howard wrote many western stories for pulp magazines such as Action Stories, Star Western, Argosy, Cowboy Stories and Western Aces, as well as other publications, but his 24 tales featuring good-natured, ridiculously strong giant Breckenridge Elkins seem to have been his most popular in the cowboy genre. These are "tall tale" westerns of a sort, nothing too grandiose ala Paul Bunyan, but definitely with tongue planted firmly in cheek. Howard gets the tone just right, and as usual for him, the stories are chock full of breathless action. Breckinridge is just a hilariously tough hombre, yet friendly, innocent and never looking for trouble...though he always seems to get into more than his fair share of it. He rides a huge, tempermental beast of a horse named Cap'n Kidd, and is a man of his word, loyal and true to a fault. So if his injured pappy tells him to go over the mountain and pick up his cantankerous Uncle Esau from the stagecoach drop in the little town of War Paint and bring him back to their family homestead for a visit, and to not take no for an answer...well, that's just what Breckenridge is going to do, come hell or high water. (From the story, "The Road to Bear Creek," originally published in December, 1934). Never having met his uncle, Breckenridge mistakenly grabs a notorious bank robber instead, and commences a very funny and frenetic string of events where "Uncle Esau" (real name, Badger Chisom) keeps trying to escape and gets the living tar pummeled out of him for his efforts. Here's a typical passage where Breckinridge and "Uncle Esau" stop off at a cabin and encounter fierce outlaw "Grizzly" Hawkins: I dropped my gun and grappled with him (Hawkins), and we fit all over the cabin and every now and then we would tromple on Uncle Esau which was trying to crawl toward the door, and the way he would holler was pitiful to hear. By the end of the story, when Breckinridge returns to his pappy's bedside with Badger Chisom, said varmint is a battered wreck. The real Uncle Esau eventually shows up and informs Breckinridge that not only has he unsuspectingly corralled famed robber Chisom, but in the process, two other bandit gangs have been laid low by the towering, youngest Elkins boy. "What are you goin' to do about me?" clamored Chisom.  There are 11 additional stories in this collection, and each one of them is similarly rambunctious in style. Aside from the two dozen Elkins tales, Howard also wrote several stories featuring ancillary characters from the Bear Creek series, plus a handful of other, non-series stories. He also penned stories about Steve Allison, known as the Sonora Kid (most of these were published in book form in 1988). The Sonora Kid also showed up in some of Howard's splendid series of historical adventure tales featuring Francis Xaviar Gordon, a.k.a. "El Borak," a former Texas gunslinger turned adventurer in 1930s Afghanistan. Unlike the other king of adventure pulps, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Howard didn't produce many novels, instead focusing on turning out a massive pile of short stories and novelettes in a very brief span (nearly all of the Bear Creek stories were published between 1935 and 1937.) Distraught over the death of his mother, Howard committed suicide at age 30, a tragic waste of an immense talent. In the nostalgia boom of the 60s and 70s, most of Howard's works were collected and published, championed by admirers like Lin Carter, L. Sprague de Camp and Glenn Lord. I've enjoyed everything of Howard's I've ever read; his work is always characterized by vivid, muscular prose, lusty, larger-than-life characters and colorful action, and it's doubtful if he ever turned out a boring paragraph or dull story - in fact, he was probably constitutionally incapable of it. In my opinion, he belongs at the very top of the heap of pulp fiction writers, along with Burroughs, A. Merrit and a handful of others - the adventure writer par excellence. My Rating: A

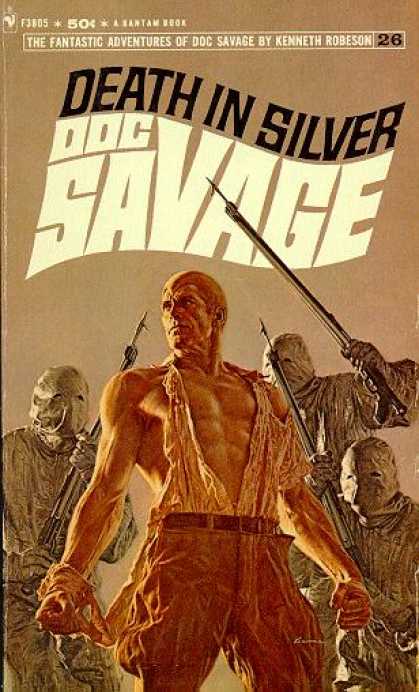

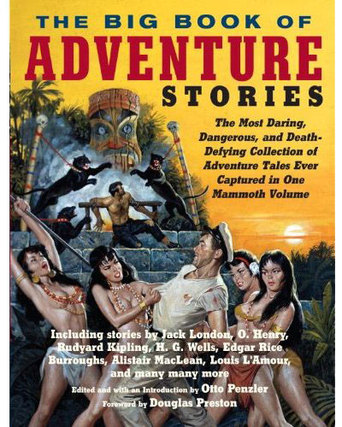

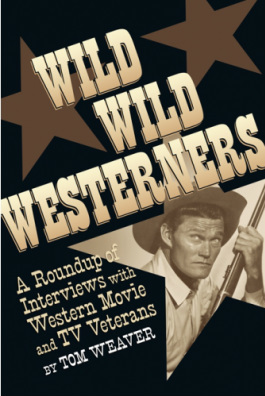

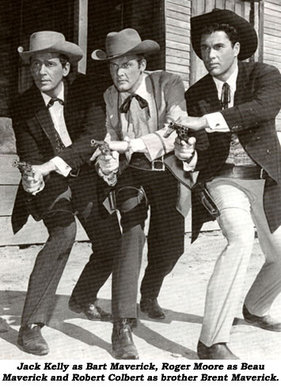

First published in February 1935, Red Snow is a good, solid Doc outing, distinguished chiefly by the truly hair-raising menace of the title. Author Lester Dent's descriptions of the effects of the "red snow," as it mysteriously appears in various locations, bringing with it agonizing, burning death, remain vivid and chilling today. Even Doc, with all his skills and forethought, quickly gains a healthy, fearful respect for the weapon. This novel marks the fairly rare case where Doc is actually on hand when the villains first start to deploy their evil scheme. Doc happens to be in Florida wrapping up some scientific research, accompanied by his perpetually-squabbling aides Monk and Ham, when the suspicious actions of a pair of fruit peddlers near his hotel draw him into the mystery. From there on out, it's one chase, fight, capture and near-death escape after another in this fast-paced adventure, as Doc races to prevent an attack on American soil by an unnamed foreign power.  While the Florida locale isn't as exotic or memorable as is usually found in these early era tales, Red Snow remains diverting reading, thanks to a non-stop parade of action scenes and intrigue. Just one example from early in the novel, as Doc escapes from a sudden shotgun attack, which clearly demonstrates Dent's mastery at describing headlong, violent action: "Doc was hanging from the windowsill by his hands. There was not much room to swing back up. It would take a moment. Dropping to the ground would be even more foolish, for there was no shelter. But there was another window below, with a window box holding flowering plants on the sill. Doc dropped. The window box broke under his weight, fell free, spilling rich black dirt and plants. But it held the giant bronze man for an instant, long enough for him to bundle his arms about his face and dive through the glass panes into the hotel room. He landed ungracefully in a shower of glass. Shotgun slugs clouted at what remained of the window sill. With a loud ripping, lead came completely through the thin wall of the hotel. It was a frame building, lightly constructed, and the automatic shotguns seemed to be charged with two or three large lead slugs to the cartridge.The guns were making thunder in the street. Doc Savage came to his feet, ran to the door, found it locked, and rammed it with a shoulder. The cheap wood panel fell off its hinges and let him through to his right. Outside, the shotguns still whooped." Top class stuff. It's this kind of writing which made the best Doc Savage pulps so compulsively readable, even when the plots or villains are not so inspired, or the final revelation behind the mystery is a letdown - not the case here. While the man behind the menace in Red Snow, the "flutelike voiced" Ark, is only moderately interesting, the plot is nicely worked out and Doc, Monk, Ham and even Monk's pet pig, Habeus Corpus, are on good form here, doling out rough justice to some pretty nasty bad guys. My Rating: B  A good anthology is a very special sort of book, one of my absolute favorite kinds; if edited well, the stories chosen wisely, the anthology is a treasure trove of delights to be read and re-read down through the years. Several terrific anthologies I've encountered in the past have not only introduced me to wonderful gems of imaginative writing, but in many cases have helped shape who I am as a reader, and cemented my taste in the kind of stories I enjoy in other mediums, such as film, TV and audio drama. Some of these formative collections include the Whispers series, edited by Stuart David Schiff; the long-running epic tomes put together by Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling, The Year's Best Fantasy & Horror; The Oxford Book of Ghost Stories; two volumes I read voraciously as a teenager, edited by Marvin Kaye: Vampires and Devils and Demons; The Rivals of Sherlock Holmes (Volumes 1 and 2) and The Rivals of H.G. Wells; Werewolf!, edited by Bill Pronzini, and many others whose titles I can't recall clearly after all these years. Now I have a new favorite to join the above ranks - The Big Book of Adventure Stories. Its contents culled from hundreds of old pulps and out-of-print collections by editor extraordinaire Otto Penzler, this mammoth trade paperback collection is loaded to the gills with colorful, exotic tales of adventure, horror, mystery and the bizarre, from well-known, oft-anthologized classics like Carl Stephenson's "Leinigen vs. the Ants" and Richard Connell's one-off "The Most Dangerous Game," to rarities from writers unfamiliar to me, like "Fire," by L. Patrick Greene (featuring the series character "the Major," who looks at first glance like a "Bertie Wooster" type but is a smooth and efficient operator indeed) or "The Golden Anaconda" by Elmer Brown Mason, one of a series of stories about "Wandering" Smith, a sort of mercenary who assists people who "want to go after something unusual in a strange place." This beast of a collection runs to 872 double-columned, small print pages, and to call the stories within action packed is an understatement. The very breadth and amorphous nature of what constitutes an "adventure" story results in an extremely varied collection; Penzler's choices give the reader a taste of the whole spectrum of adventure fiction. The book is divided into several sections along these sub-genre lines, lesser-known works and fresh discoveries sitting cheek-by-jowl with those by more famous writers. For example, the "Sword and Sorcery" section includes a Ffafhrd and Grey Mouser tale from Fritz Leiber, "The Seven Black Priests," as well as a Conan gem from Robert E. Howard, "The Devil in Iron," along with works by Harold Lamb and Farnham Bishop and Arthur Gilchrist Brodeur. Other sections include: "Man vs. Nature," "Island Paradise," "Sand and Sun," "I Spy," "Yellow Peril," and "In Darkest Africa." There are also science fiction tales, western stories (including a Hopalong Cassidy short), grisly horror yarns (check out Clark Ashton Smith's nasty example of two explorers encountering That Which Should Be Left Alone in "The Seeds of the Sepulchre") and more.  Fans of these sorts of blood-and-thunder, rip-snorting tales of action and daring will doubtless recognize the names included here: Rudyard Kipling, Grant Stockbridge (with a nifty little tale that shows how his vigilante pulp hero, Richard Wentworth, a.k.a. "The Spider," got his start in crime-busting), Jack London, Saki, H.G. Wells, main "Doc Savage" author Lester Dent, Louis L'amour, Talbot Mundy, P.C. Wren, O. Henry, Ray Cummings, Damon Knight, Alistair MacLean, H.C. McNeile (with a Bulldog Drummond story), Baroness Orczy, Rafael Sabatini, Sax Rohmer, John Buchan, H. Rider Haggard, Cornell Woolrich, and Edgar Wallace. And, as a delicious icing on this enormous cake, the anthology bows out with a complete Tarzan novel by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Tarzan the Terrible. Balancing all these well-known masters are a score of other authors of decided merit whose names and fame have not had the good fortune of continuing far beyond their deaths, like the above luminaries. These rarely seen and anthologized tales add a nice sense of discovering new terrain to the collection, tinged with the bittersweet knowledge that more stories from these same authors may well be nigh impossible to track down. All in all, this is a truly indispensable, one-stop-shopping anthology, ideal for someone just dipping their toes into the old-school pulp adventure waters, as well as the more seasoned reader of such prose, who should find lots of new material here to dive into and relish. Additional pluses are Penzler's interesting (if in some cases, tantalizingly brief) one-page author bios which precede each story, and a number of illustrations that once accompanied the stories in the original magazines in which they were published. With 46 stories and a complete novel, you certainly get more than your money's worth with this collection. And for those fond of old-fashioned, breathless, thrill-a-minute storytelling, these are tales in which, as Douglas Preston states in his introduction, "things move."  Penzler's other Vintage Crime/ Black Lizard giant anthologies are equally recommended: The Black Lizard Big Book of Pulps and The Black Lizard Big Book of Black Mask Stories. Penzler and Vintage Crime have also subsequently published other equally large and diverse collections: The Big Book of Ghost Stories (got this puppy on order now), The Vampire Archives, Zombies Zombies Zombies!, and The Big Book of Christmas Mysteries. You can't go wrong with any of these big, juicy doorstoppers, sure to provide hours and hours of reading pleasure. My Rating: A+  A good Q & A interview piece is a work of art, and what might seem pretty easy and straightforward on first glance actually isn't. It takes a good deal of skill and research to come up with good, memorable questions to get the subject of the interview to open up and hopefully deliver some tasty nuggets of backstage, bird's-eye-view history. Tom Weaver is a past master of this kind of interview format, having spent much of the past 30 years talking to many lesser-known, overlooked - or sadly, in some cases, mostly forgotten, by all but the most diehard movie aficionados - actors, actresses, writers, directors, producers, etc., ranging from those who worked on big Hollywood studio A-level projects, to the many who toiled thanklessly in the B-movie, cult, fringe and independent movie world. Weaver's usual purview is 1930s - 1950s horror and science fiction cinema (perhaps his most famous book being the wonderful Universal Horrors, co-authored with Michael and John Brunas), but he also has published many interviews with people who have worked heavily in the western genre as well. Back in the day, there was a lot of genre cross-pollination with studio employees, and so both in front of camera and behind-the-scenes personnel would often hop around, working hard churning out all manner of straight dramas, horror films, crime flicks, sci-fi monster mashes and, yes, shoot-'em-up cowboy pics. Weaver, in the process of interviewing those who worked on various sci-fi and horror films which are his bread-and-butter, doubtless had a chance to get plenty of additional material about their work in other genres. Most of the interviews in the catchily-titled Wild Wild Westerners: A Roundup of Western Movie and TV Veterans, first appeared in Western Clippings magazine, and nearly each one is a delightful read, full of fun anecdotes and engaging reminiscences about the making of many classic TV and movie westerns. Highlights include: * Kenneth Chase' recollections of working on The Wild Wild West (where he was responsible for bringing to life many of the disguises donned by secret agent extraordinaire Artemus Gordon (Ross Martin), partner of James West (Robert Conrad). * Ed Faulkner warmly recalls his time acting alongside big "Duke" Wayne, in films like McClintock, The Undefeated, The Green Berets and Hellfighters.  * Robert Colbert, best known as one half of the time traveler team on The Time Tunnel, dishes candidly and with good humor in an all-too-brief but splendid piece about his abortive appearance as brother Brent on Warner Bros.' seriocomic gem, Maverick: "You couldn't buy a vacation like any one of the western shows I did. Just bein' out there in the wide open spaces with great guys and horses and beautiful women and good food...and then you got paid for it. Not much, but you got paid!" (1) * Andrew J. Fenady, writer/producer of the fine western series The Rebel, starring Nick Adams, goes into fascinating detail about making that show and his complex lead actor (and friend). One sample: "I sure as hell am not ashamed to put my name alongside The Rebel. In some ways it was completely different and ahead of its time. I'm not going to say it was a work of art, but it certainly came from the heart." (2) * Pat Fielder, the woman who wrote the screenplays for such fun sci-fi/ horror flicks as The Monster That Challenged the World, The Vampire, The Flame Barrier, and The Return of Dracula (not to mention Geronimo with Chuck Connors), discusses her work on TV's famous western The Rifleman. * A lengthy and lively Q & A with the man forever known as Davy Crockett (and to a lesser extent, Daniel Boone), Fess Parker.  Telly Savalas menaces Paul Picerni in THE SCALPHUNTERS. Telly Savalas menaces Paul Picerni in THE SCALPHUNTERS. * Paul Picerni relates some unbelievable anecdotes about his co-stars in The Scalphunters, Burt Lancaster and Telly Savalas. Other interviewees include Robert Clarke, June Lockhart (who has nice things to say about the roster of TV leading men she co-starred with, from Richard Boone to Chuck Connors to James Arness and Ward Bond), Bill Phipps, Ann Robinson, Maury Dexter and Paul Wurtzel, and many others. My only complaint about the book is it's too short (at 197 pages, less than half as long of the usual Weaver interview collection), and I flew through it all too quickly - it was that entertaining. In other words, I wanted more! Weaver does his homework and generally avoids obvious, boring questions, and the results speak for themselves. These pieces are loaded with fun background facts and stories about some big-name stars in the western pantheon, and, taken together, create a vivid picture of what it was really like making movies once upon a time in Hollywood's dream factory. Highly recommended, as are Weaver's many other similar books on sci-fi and horror cult filmmakers. My Rating: A - Source Note: (1) and (2) excerpted from Wild Wild Westerners: A Roundup of Interviews with Western Movie and TV Veterans, by Tom Weaver, published by BearManor Media, 2012.

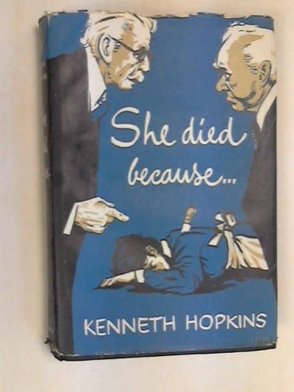

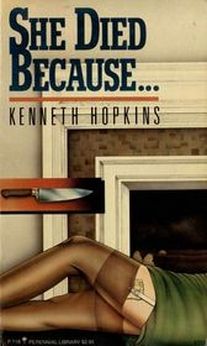

Kenneth Hopkins pretty much seems to be a forgotten author, which is a shame, really, as his comic mystery novels featuring the elderly amateur sleuths Dr. William Blow, 81, and Professor Gideon Manciple, 79, are quite witty, fun and nicely-plotted things. The opening of She Died Because... is delightful, as the absent-minded, quotation-loving bachelor Dr. Blow - "his mind...still mainly occupied with the problems of editing the text of the whole works of Samuel Butler, a task upon which he had now been engaged for some fifteen years" - comes to the gradual realization that he's hungry. It's 3 a.m. and he hasn't had his tea, so he goes in search of his housekeeper (whom he calls Mrs. Solihull, even though that's not her real name...Dr. Blow just finds it easier to call all his housekeepers - he's had many over the years - Mrs. Sollihull). After some hesitant poking around, Blow arrives at the door to Mrs. Sollihull's room, and after calling her name several times, tentatively opens the door: Dr. Blow didn't care, yet, to venture in. A man might in emergency open his housekeeper's door. But it was hardly his business to enter, especially if she were not there. At least, she made no answer.  It isn't until Blow rouses his good friend and neighbor, Prof. Manciple, to come have a look that the pair discover that Mrs. Sollihull is in actual fact dead, her mouth open and a knife sticking out of her back. The pair do what all respectable British gentlemen would do at such a time - they make themselves some tea, then telephone for the police. But when Inspector Urry arrives on the scene, the murder weapon is no longer there. Soon the elderly duo are nosing around the case, led by the vastly more worldly and capable Manciple. Before they know it, they're up to their necks in a "domestic service" theft ring, prostitution, illicit night clubs, and other criminal enterprises. While the mystery itself is well-enough plotted, what exactly lies behind the death of Mrs. Sollihull, a.k.a. "Flash Elsie," proves less interesting than following the very engaging antics of the bumbling pair of over-age sleuths. Hopkins was obviously an erudite man in real life, for he captures the dry, tweedy donnishness of the scholar's lifestyle and habits quite well. The novel is full of the sort of wry wit that I find irresistible. I was reminded of that wonderful British series Charters & Caldicott that ran on PBS' Mystery! series back in the mid 80s, which also featured a pair of elderly, bickering sleuths, this time cricket fanatics rather than scholars, who perhaps cause more havoc than help in the official murder inquiries. She Died Because... was originally published in 1957. I have the paperback reprint from Perennial Library, first published in 1984, as well as another Blow and Manciple novel, Body Blow (1962), from the same publisher. There's also at least one other caper featuring the pair published in paperback from Perennial, Dead Against My Principles (1960). Hopkins wrote a handful of other mysteries, including a spy novel, Amateur Agent (1955), published under the pseudonym "Christopher Adams." Not a lot seems to be known about Hopkins, but some excellent info can be found here at the interesting blog, Existential Ennui. Judging from this novel, at least, Hopkins deserves to be better known. In Dr. Blow and Prof. Manciple, he created a worthy pair of amateur detectives, and I look forward to catching up with more of their misadventures in the future. My rating: A- |

Welcome to the Armchair...

Look out the window. It’s a dark, cold, rainy day. Too nasty to go outside.

Better stay inside, read a good book. There’s a bookcase over to your left. Run your fingers over the spines. Books of all shapes, sizes and genres; hardbacks, paperbacks. Take your time browsing through the titles. No rush. Find something that feels just right. Now turn around. Over in the corner is a beat-up, black leather armchair. The leather is faded and cracked in places, the cushions battered. This chair has seen better days. But boy, does it look inviting... Next to the chair is a standing lamp and a small table. Plenty of room for a nice cup of tea, a plate of cookies, whatever’s your poison. So switch on the light, settle down with your book, open to page one, put your feet up, and let the author whisk you away to another world. Hey!

Be sure to subscribe to the RSS feed below, to be informed of new postings! Reading Blogs

My Reader's Block

Tipping My Fedora Killer Covers Pattinase At the Scene of the Crime Existential Ennui Complete Disregard for Spoilers Traditional Mysteries The Passing Tramp In Search of the Classic Mystery Novel Useful Websites

The Charlie Chan Family Home

The Agatha Christie Official Website The Stone House (The Gladys Mitchell Official Site) Categories

All

Archives

October 2014

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed